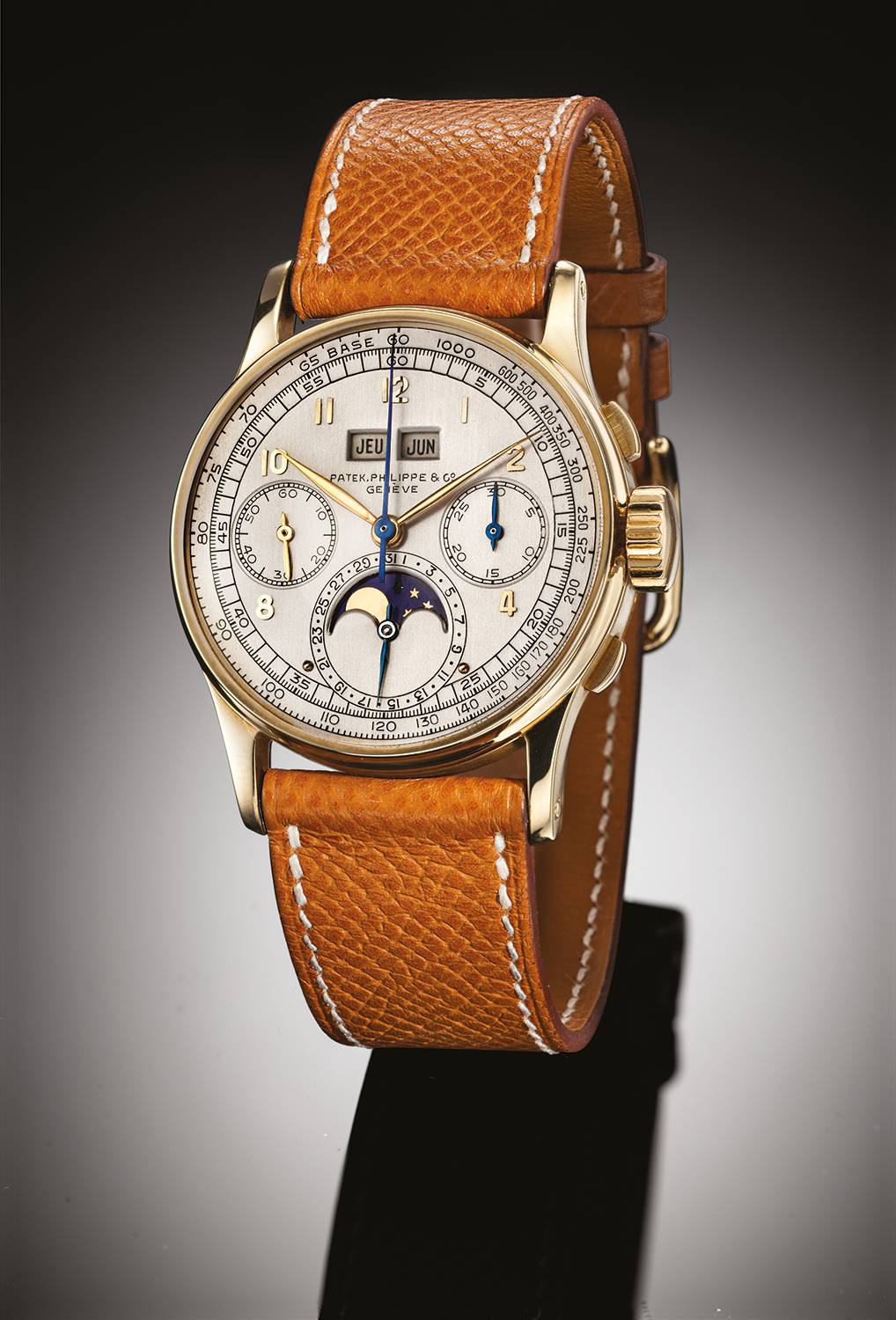

Tempo é uma das relações mais complicadas que cultivamos. Ou que evitamos cultivar, como se fosse possível fugir do destino final. Há quem ore a ele, Caetano. Há os devotos de Aion e de Kairós que, num desejo de liberdade e de sintonia com a natureza, fogem do Khrónos como o diabo foge da cruz e, no lugar do tempo corrido, consultam apenas o Sol e a Lua, o ciclo das estações. Dreamers, you may say, mas eu sei que não sou a única. Do outro lado, correm em velocidade da luz aqueles para quem tempo é dinheiro, e que, no lugar de tic-tac-tic-tac, ouvem ca-tchim-ca-tchim. Tem os coelhos de Alice, para quem os ponteiros são a eterna ameaça de perder o bonde da história, que resfolegam diante do turbilhão do “tarde, tão tarde até que arde”. Obcecados por controlar a precisão da passagem dos segundos, constroem, desde o século XIX, tourbillons, à espera de que a vida não escorra pelas mãos — e têm eles herdeiros legítimos, engenheiros de alma, fascinados por um mecanismo que segue o mais cobiçado da relojoaria mesmo que, em termos de tecnologia, ele seja coisa do passado. Deles há também os herdeiros testamentários, que não distinguem relógios de Ferraris, la bella macchina, arrematados em leilões por 11 milhões de dólares (preço do Patek Philippe Henry Graves Supercomplication, um recorde de Daryn Schnipper, a vice-presidente sênior da divisão internacional de relógios da Sotheby’s, num mundo dito de homens). As cifras cheias de zeros criaram também o mercado de investidores para quem o relógio (não) pode mofar na caixa até o momento certo de ser vendido, quando o máximo de zeros é acrescentado antes da vírgula. E há Pierandrea Sabbadini. Ele é um pouco e nada disso ao mesmo tempo. Um tipo à parte. Singular.

Foto: Divulgação

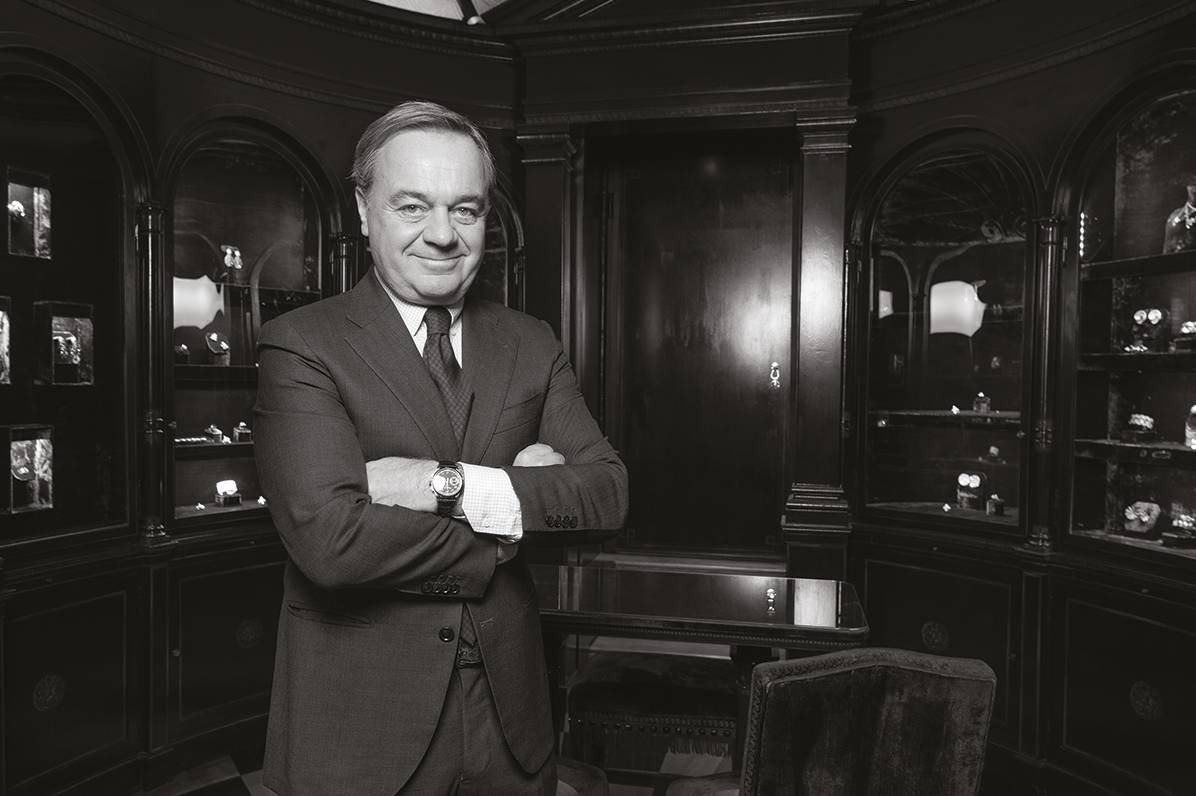

“Não tenho nenhuma relação particular com o tempo”, afirma. Com ele, a experiência é flexível. No início, ele estava disponível a qualquer minuto para conversar sobre como virou o Indiana Jones dos colecionadores, para quem o Santo Graal da relojoaria está entre os Patek Philippe e os Rolex manufaturados entre as décadas de 1950 e 1980. “Indiana Jones?”, ele ri. “Melhor do que ‘autoridade’, que é uma big word e me dá mais importância do que mereço.” Uma viagem com clientes para Monte Carlo, no dia seguinte, limitou o “anytime” para certos horários. Logo, as impossibilidades eram muitas. Cravamos: antes do jantar. Na hora “H”, Sabbadini pediu mais tempo. Quinze minutos viraram meia-hora. Nesse intervalo entre as conversas, ele já estava de volta a Milão. Se sua relação com o tempo é descomplicada, a relação com os relógios, essa sim, é particular. “É um amor que virou negócio, mas que continua sendo, acima de tudo, amor.”

Como todo amor, precisou de tempo e de espaço para acontecer. Pierandrea é a quarta geração da joalheria Sabbadini, conhecida por passear sem complexo entre a tradição e a modernidade da joalheria italiana. Diamantes, rubis, esmeraldas e safiras aparecem em settings de materiais heterodoxos como cerâmica e aço. A assinatura da casa é a coleção Ape Sabbadini: uma abelha de asas abertas, cobertas por um pavê de diamantes, e corpo, entre muitas outras opções, de pavê de safiras amarela e negra, que aparece em anéis, brincos, broches e pingentes. Pedras são a especialidade de Pierandrea, formado em gemologia. Joias, além da linhagem, foram seu primeiro emprego depois de formado. Ele entrou para o departamento de joalheria da Sotheby’s. “Nunca antes alguém do ramo tinha sido aceito no cargo. É uma questão de confidencialidade, de não ter acesso a informações privilegiadas para passar para frente.” Sabbadini tinha 22 anos. O departamento de relógios, comandado por Daryn Schnipper, a “garota” do Patek recorde, era a pedra obrigatória no seu caminho até a sala do departamento de joalheria. Ele passou a chegar primeiro 15, depois 20 minutos antes do expediente para olhar as vitrines com os timepieces. “Daryn me transmitiu tudo o que sei.”

Foto: Divulgação

De volta a Milão e diante dos Sabbadinis, uma família sem afeição por relógios — o pai, Alberto, usa Swatch, e só tem um Rolex e um Patek para não decepcionar o filho –, Pierandrea decidiu aplicar os ensinamentos da temporada na casa de leilões e comprar e vender relógios vintage. O primeiro foi um Rolex GMT de aço dos anos 1970, que “agora a gente encontra em todo lugar”. Aos poucos, ele foi criando boa reputação por garimpar relógios de exceção, com efeito “oomph”, como ele diz. De boca em boca, foi formando uma clientela e hoje tem uma coleção de modelos de Patek Philippe e Rolex vintage, cuja produção foi interrompida. “O mercado está saturado de negociantes que correm atrás de coleções particulares, e compram de volta o que acabaram de vender. Isso não me interessa”, diz. “Prefiro criar amizade, uma relação que vai além do comércio.” A linha entre a compra feita para si mesmo ou para começar a coleção de um cliente é tênue. Muitas vezes, o que é seu vai para outro punho e, anos depois, volta para casa. “Poderia comprar um relógio por dia, mas, se o objeto não me provoca uma emoção especial, deixo passar.” A coleção fica à venda na joalheria da Via Montenapoleone, em Milão, parte exposta no andar de baixo da vitrine. “Enquanto as mulheres escolhem as joias, os maridos se entretêm com os relógios.”

Como bom negociador, Pierandrea não se recusa a vender um relógio para um investidor, mas sente um aperto no coração de saber que o relógio não passa de uma commodity. Se puder, desliza uma ou outra palavra educativa sobre o valor, no outro sentido da palavra, da peça. Mais doído mesmo, para ele, é quando os relógios são mantidos em cativeiro, por assim dizer. Comprados para morarem em cofres, sem jamais sair para passear - o contrário do que acontece com os 26 exemplares de sua coleção particular, vistos no Samanah Golf Club, aos pés do Atlas, em Saint Moritz, ou em Porto Cervo, na Sardenha, que, de destino tão frequente, virou tema de coleção da Sabbadini. “Eu vejo um relógio como eu vejo uma pedra; é a minha grande paixão, muito mais do que a joalheria”, diz. “Cada um tem uma história, uma caixa, notas e documentos de lojas em línguas diferentes. O que me move é recriar essas histórias.” Sabbadini conta que, na manhã do dia em que conversamos, ele estava em Mônaco diante de dois Rolex de ouro. O primeiro, número de série 485523, datava de 1939. O segundo, série 485524, datava de 1941. Ambos vinham da mesma loja em Roma. “Imagine isso, em plena guerra, o mesmo modelo, manufaturado com dois anos de diferença, e eles são sequenciais e vendidos no mesmo lugar. Quais as chances de isso acontecer? Quem eram essas pessoas, como era possível dispor desse dinheiro e ter essa vontade num período de exceção? É inacreditável.” De repente, o tempo para, os anos e os personagens citados se misturam. Sabbadini não teria, além de Indiana Jones, um quê de Alexandre Grouet, que escreveu a ficção Une Course Contre la Montre, sobre o universo da relojoaria e seus colecionadores? Talvez ele ainda não tenha se dado conta, mas cultiva, sim, uma relação particular, talvez uma das melhores, com o tempo: romance. Penso imediatamente no relógio de pé, feito pelo suíço Samuel Roy (1746-1822), que fica na antecâmara do apartamento de Napoleão Bonaparte no Château de Fontainebleau, restaurado há dois anos pela política de mecenato da Rolex. Ele tem dez mostradores com indicações sobre o tempo e a astronomia. É possível ler a hora, o dia da semana, o mês, saber se estamos ou não em ano bissexto, e também as fases da Lua e do Sol, a estação do ano e o signo do dia no zodíaco. Graças a Sabbadini, me dou conta de que é possível conciliar-se com Khrónos. E viver uma história de amor com ele.

Foto: Divulgação

A matéria "Ao Sabor das Horas", publicada originalmente na edição 01 da Numéro Homem, foi atualizada às 20h do dia 08 de fevereiro de 2024 nesta versão digital.

ENGLISH TEXT

As the hours go by Pierandrea Sabbadini allows himself to postpone appointments and splits his time between golf and ski seasons, vacations on the Costa Smeralda, sales in Monaco and working at the family jewelry store on Via Montenapoleone. He has become the best-kept secret among collectors chasing Rolex and Patek Philippe watches issued between 1950 and 1980.

Our relationship with time is a complex one. But we tend to avoid dealing with it, as if it were possible to escape the final destination. There are those who pray to it, Caetano. There are devotees of Aion and Kairós who, in their desire for freedom and harmony with nature, avoid Khrónos like a vampire avoids garlic, consulting only the Sun and the Moon, the cycle of the seasons. Dreamers, as one might say. On the other hand, those for whom time is money are running at the speed of light and who, instead of tick-tock-tick-tock, hear ka-ching-ka-ching. There are Alice’s rabbits, for whom the hands of the clock are the eternal threat of missing the train of history, who gasp at the whirlwind of “I’m late! I’m late! I’m late!” Obsessed with controlling the precision of seconds passing, they have been building tourbillons since the 19th century, hoping that life wouldn’t slip through their hands - and they have legitimate heirs, engineers at heart, fascinated by a mechanism that is the most coveted in watchmaking even if, in terms of technology, it is a thing of the past. There are also the testamentary heirs, who don’t distinguish between watches and Ferraris, la bella macchina, sold at auctions for 11 million dollars (the price of the Patek Philippe Henry Graves Supercomplication, a record set by Daryn Schnipper, senior vice-president of Sotheby’s international watch division, in a so-called man’s world). The figures full of zeros have also created a market of investors for whom the watch can (not) sit in its box until the right moment to be sold, when the maximum number of zeros is added. And then there’s Pierandrea Sabbadini. He’s a little bit of this, and none of it, all at the same time. A guy apart. Singular.

“I have no special relationship with time,” he says. It’s true. With him, the experience is flexible. Initially, he was available at any minute to talk about how he became the Indiana Jones of collectors, for whom the Holy Grail of watchmaking lies between the Patek Philippe and the Rolex manufactured between the 1950s and 1980s. “Indiana Jones?” he laughs. “Better than ‘authority’, which is a big word, more of a big deal than I deserve.” A trip with clients to Monte Carlo the following day limited his “anytime” to a few specific hours. Soon, the impossibilities were many. We settled on before dinner. At the time we had scheduled, Sabbadini asked for more time. Fifteen minutes turned into half an hour. In the interval between conversations, he was already on his way back to Milan. If his relationship with time is careless, his relationship with watches is private. “It’s a love that has become a business, but which remains, above all, love.”

Like all love, it took time and space to happen. Pierandrea is the fourth generation of the Sabbadini jewelry house, known for its uncomplicated walk between tradition and modernity in Italian jewelry. Diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires are set in heterodox materials such as ceramic and steel. The house’s signature is the Ape Sabbadini collection: a bee with wings spread, covered in a pavé of diamonds, and a body, among many other options, made of yellow and black sapphire pavé, which appears in rings, earrings, brooches, and pendants. Stones are the specialty of Pierandrea, as a gemology graduate. Jewelry, in addition to his lineage, was his first job after graduating. He joined Sotheby’s jewelry department. “Never before had someone from the industry been accepted into the position. It’s a matter of confidentiality, of not having access to privileged information to pass on.” Sabbadini was 22 years old. The watch department, headed by Daryn Schnipper, the “girl” of the record-setting Patek, was the mandatory stepping stone on his way to the jewelry department. He started arriving 15, then 20 minutes before work to look at the timepieces in the showcases. “Daryn has taught me everything I know.”

Back in Milan and faced with the Sabbadinis, a family with no affection for watches - the father, Alberto, wears Swatch, and only has a Rolex and a Patek so as not to disappoint his son -, Pierandrea decided to apply the lessons of the season at the auction house and buy and sell vintage watches. The first was a steel Rolex GMT from the 1970s, which “you can find everywhere now”. Little by little, he developed a reputation for collecting exceptional watches, with an “oomph” effect, as he puts it. Through word of mouth, he built up a clientele and now has a collection of Patek Philippe and Rolex models whose production has been discontinued. “The market is saturated with dealers who chase after private collections and buy back what they’ve just sold. I’m not interested in that,” he says. “I prefer to establish a friendship, a relationship that goes beyond commerce.” The line between buying for yourself or starting a client’s collection is thin. Often, what is yours goes to someone else and, years later, returns home. “I could buy a watch every day, but if the object doesn’t spark some special feeling in me, I let it go.” The collection is on sale at the Via Montenapoleone jewelry store in Milan, part of which is displayed downstairs in the shop window. “While the women choose the jewelry, the husbands entertain themselves with the watches.”

As any good negotiator, Pierandrea doesn’t refuse to sell a watch to an investor, but he feels a squeeze in his heart knowing that the watch is nothing more than a commodity. If possible, he’ll slip in a word or two about the value, in the other sense of the word, of the piece. What really hurts him is when the watches are held captive, so to speak. Bought to live in safes, never to go out for a walk - the opposite of what happens with the 26 pieces in his private collection, seen at the Samanah Golf Club, at the foot of the Atlas Mountains, in Saint Moritz, or in Porto Cervo, in Sardinia, which, from being such a frequent destination, has become the subject of one of Sabbadini’s collections. “I see a watch like I see a stone; it’s my great passion, much more than jewelry,” he says. “Each one has a story, a box, notes and store documents in different languages. What drives me is to recreate these stories.” Sabbadini says that on the morning of the day we spoke, he was in Monaco in front of two gold Rolexes. The first, serial number 485523, dated from 1939. The second, serial number 485524, dated from 1941. Both came from the same store in Rome. “Imagine that, in the midst of war, the same model, manufactured two years apart, and they are sequential and sold in the same place. What are the chances? Who were these people, how was it possible to have this kind of money and will in such an exceptional period? It’s unbelievable.” Suddenly, time stops, and the years and characters mentioned blend together. Does Sabbadini not, in addition to Indiana Jones, have a touch of Alexandre Grouet, who wrote the fiction Une Course Contre la Montre about the world of watchmaking and its collectors? Perhaps he has not yet realized it, but he does have a special relationship, perhaps one of the best, with time: romance. I immediately think of the clock made by Samuel Roy (1746-1822), located in the antechamber of Napoleon Bonaparte’s apartment at the Château de Fontainebleau, restored two years ago through Rolex’s sponsorship policy. It has ten dials with indications about time and astronomy. You can read the hour, day of the week, month, find out if it’s a leap year or not, and also the phases of the Moon and the Sun, the season, and the zodiac sign of the day. Thanks to Sabbadini, I realize that it is possible to reconcile with Khrónos. And to have a love story with him.

The article "As Hours go By", originally published in the 01 edition of Numéro Homem, was updated February 8th at 8PM in this digital version.